Why is Some Insulin Available Over the Counter?

The evolution of Federal and State drug regulation resulted in early insulins being grandfathered into Over the Counter status

There’s been a resurgence of interest in non-prescription insulin, no doubt a result of the high prices for the most widely dispensed-by-prescription branded analogs and a political climate that’s breeding uncertainty over the continued availability of insurance for people with diabetes. People have been turning to old-line products, such as Lilly Humulin and Novo-Nordisk Novolin, and Walmart’s store-branded ReliOn products, or at least researching whether such lower-cost brands are an option.

Why is a prescription for Novo Novolin, one of the products supplied under the ReliOn brand at Wal-Mart, available just for the asking if Novo’s Novolog is not? To begin to understand why and why not, it’s useful to look at how the federal and state public health agencies have historically approached drug safety and effectiveness.

Read more: Why Walmart insulin isn’t the answer.

Federal Regulation

The insulin varieties that are available today can trace their lineages back to the days before there was a U.S. Food and Drug Administration, and before many states had pure food and drug laws, professional pharmacists’ codes, or regulations restricting distribution of medicinal products. Pretty much all that was required in the 1930s to lawfully manufacture insulin for sale was the right to do so under the Banting patent and a manufacturing facility meeting the U.S. Agriculture Department’s standards for cleanliness. In the beginning, there was one U.S. patent holder — Eli Lilly — and one Lilly plant in Indianapolis extracting insulin from material shipped from slaughterhouses. As long as those responsible for mixing the batches took proper steps not to let impurities in and the label accurately reflected the contents of the vial, the insulin could be sold anywhere in the United States, without the need of a doctor’s prescription.

What is now known as the federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act came into existence in 1906 as the Pure Food and Drug Act, at a time when the rationale underlying regulation of the pharmaceutical industry was to prevent the makers and sellers of medicinal products from contaminating them with cheap or phony ingredients or making false or misleading claims about their therapeutic value. Medicinal remedies came from plants or minerals or were vaccines made using animal products. There was no such thing as a synthetic, analog, or biosimilar drug.

In 1906, the bureau within the U.S. Department of Agriculture that regulated pesticides and meat-packing plants was given the power to stop interstate commerce in impure, dangerous, or falsely advertised drugs. By 1938, when a revision to the law created the forerunner agency to the Food and Drug Administration, insulin extracted from agricultural animals had already been in wide use for about 15 years in Canada, Europe, and the U.S. Its safety and value as a therapy had been shown, beginning in human trials as a matter of fact, and so it wasn’t a “new” drug that required a demonstration before the FDA that it was safe to market in the U.S.

In 1941, Congress passed the Insulin Amendment to the Food and Drug Act, requiring insulin sold in interstate commerce to pass a batch-by-batch certification of purity under what was essentially a quality assurance standard enforced by the FDA. States which had by then adopted their own pure food and drug laws permitted sales within their borders of insulin which had met the federal batch certification requirement. It would not be until 1951 when Congress passed the Durham-Humphrey Amendment to the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (“FDA Act”), that the U.S. government got into the business of determining what drugs may be sold only by prescription, and of creating the category of “legend drugs.”

Read more: How insulin became so expensive – a history

A “legend” drug is not one that’s been around long enough to be legendary, nor is it a new type of party drug. The “legend” is the text on the package label, specified by the United States Code to read, at a minimum, “Rx Only” for prescription drugs. Conforming state laws often expand the terminology to require wording such as “prescription required by federal law,” “number of refills limited to …,” “veterinary use only,” and the like.

Then, in 1962, the FDA Act was once again amended to empower the agency to require proof of effectiveness for new drugs before their introduction to the market, and this ushered in the era of multi-stage clinical trials prior to issuance of a new drug, device, or clearance for use of an existing drug, and the requirement for post-market trials and adverse event reporting. Under the FDA Act in its current form, and the accompanying regulations for clearance and then commercial distribution, an applicant for a new drug approval must state in detail all clinical considerations bearing upon whether the product ought to be used only under medical supervision.

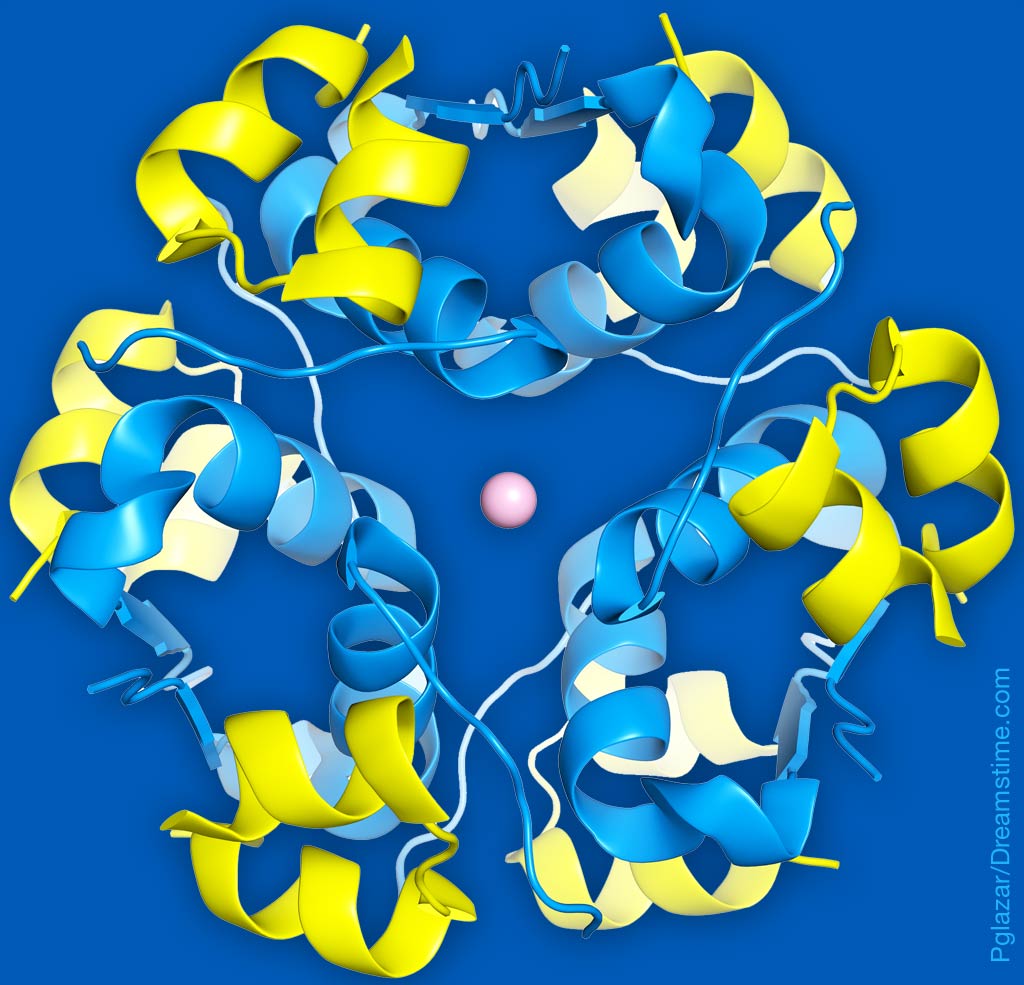

Medical supervision as a concept extends to the determination of appropriateness for the patient, and determination of dosage, and to guard against the risks associated with misuse or use in combination with other medications. The nature of modern pharmacological practice is to target specific disorders of the autoimmune, metabolic, circulatory, nervous, and other systems of the body with ever more synthesized drugs having sophisticated mechanisms of action.

So, in the existing regulatory environment, as pharmaceutical developers introduce diabetes products that have undergone exotic manipulations of amino-acid chains to achieve better patient outcomes (and achieve extended patent protection) it’s a given that a product will have the “Rx Only” legend when it’s cleared by the FDA, unless there is a specific reason to exempt it.

State Regulation

The dispensing of prescription drugs and controlled drugs (such as narcotics to relieve pain) and the practice of professional pharmacy have always been regulated under state, District of Columbia and U.S. Territorial law (lumped together as “state law” for purposes of this article). How each jurisdiction regulates insulin sales is a matter of its drug safety, insurance policies, and tax laws. Under state statute or regulation, insulins are dispensed either as legend drugs or as permitted for non-prescription drugs.

The term “over the counter” for non-prescription insulin is not accurate. “Behind the counter” would be a better way to describe the insulin available without a prescription, because all state laws that allow non-prescribed insulin require it to be kept separate from true over-the-counter products. Although it varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, all states also restrict access to hypodermic needles and syringes but relax their restrictions (usually by number over a weekly or monthly period) for needles and syringes furnished to people who need to inject insulin. Every state restricts retail insulin sales to licensed pharmacies, under the supervision of a registered pharmacist, even if the insulin itself needs no prescription.

The Special Case of “Human Insulin”

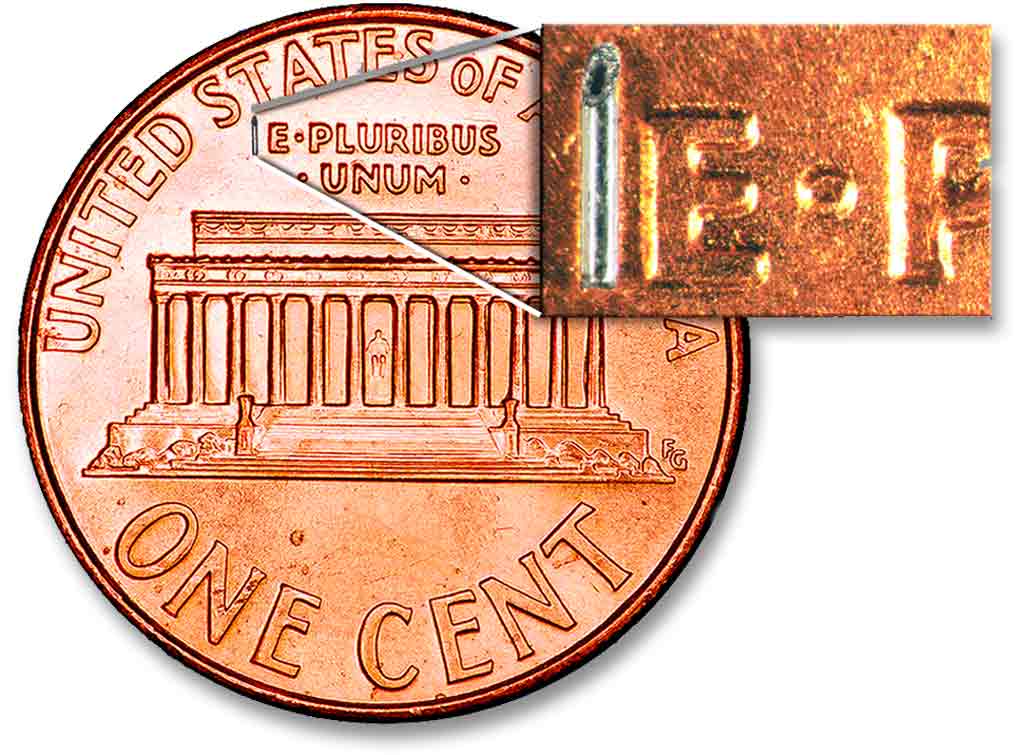

Insulin made from animal pancreatic material differs only slightly from insulin produced by the human pancreas, and that difference is in the number of molecules in the protein chain. Scientists first began to contemplate non-animal insulin products because it was thought by some that the supply of pig pancreases would over time fail to cover the demand for insulin to treat human diabetes. There was also a desire to eliminate allergic reactions to an animal-derived product and to develop a product of more consistent potency, and to create insulin which could more closely mimic the insulin secreted by a healthy human pancreas throughout the day.

These dual desires led researchers to start combining human DNA with a microorganism which could reproduce itself and manufacture insulin. Of course, such a breakthrough also meant that manufacturers such as Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi could stop buying railcars of a slaughterhouse by-product that at best yields a raw-material-to-finished-product ratio of 2 tons pig pancreas to 8 ounces of purified insulin.

Eli Lilly went about working with the biopharma company Genentech in the late 1970s to develop a process using recombinant human DNA and gut bacteria to derive a product that would mimic the basal and prandial insulins secreted in the healthy human pancreas. At approximately the same time, Novo had been working on a similar project using yeast as the self-reproducing microorganism to host human DNA coding for insulin production and churn out the bioequivalent of insulin produced by a human pancreas. When these products went to the FDA for clearance, the developers successfully demonstrated that their discoveries so closely resembled the predecessor insulins — in their biochemical makeup, mechanism of action, and method of administration — that users needed no additional protections than had been offered under the 1941 Insulin Amendment and then-existing FDA regulation. These products, although they fit the bill as “new” drugs, were therefore found to be exempt from the legend drug labeling requirement. Lilly’s Humulin went on the U.S. market in 1982, and Novo followed in 1988 with its entry Novolin. These remain the only two of the Big Three insulin manufacturers to market non-prescription insulin in the U.S.

In 1997, the Insulin Amendment to the FDA Act was repealed, and replaced with an amendment to the Act to address importation to the United States of insulin produced by foreign makers. Novo, based in Denmark, and Sanofi in France have U.S. affiliates to manufacture and market their diabetes care products. That change left the authority to the states to enforce prescription requirements upon insulin products not requiring a prescription as legend drugs under federal law. Near as we can determine, only one state, Indiana, has decided that insulins can only be available by prescription.

Whether one should get insulin “over the counter” in the other 49 states and the District of Columbia is another matter and one that a person with diabetes should discuss with a doctor. Certainly, older generation insulin is better than no insulin at all if a prescription expires or one runs out of money for steep copays, but such insulin should be used with caution and overseen by professional medical care.