Dear Slate: The Real Cultural “Myth” of Insulin’s Discovery is the Overstated Effects of the Drug

As the Editor of Insulin Nation and the mother of a young child with Type 1 diabetes, I was very encouraged to come across Slate’s short documentary on “Dr. Banting’s Miracle Drug,” published on January 4, 2018. This makes the publication’s second story on diabetes in a two-week period. (At the end of December, Slate staff writer Jacob Brogan wrote a very compelling piece about his experiences with CGM technology.) The tagline for the documentary is this: “A hundred years ago, a diagnosis of Type 1 diabetes meant certain death for children. Insulin changed that—and spurred a powerful myth.”

Sounds promising, right? But, ironically, in the process of unveiling one powerful myth, the film spurred another one. Its primary purpose is to undo the narrative of Dr. Frederick Banting’s “miracle” by demonstrating the critical contributions of other scientists who came before and worked alongside Banting. Banting’s biographer, Michael Bliss, plays a prominent role. Bliss suggests that James Collip, the University of Toronto scientist who purified Banting’s crude insulin extract, had more to do with the discovery of insulin than history acknowledges. He further suggests the reason for Banting’s appeal: the public loves the change-of-circumstances story.

Banting was a middle-class farm boy who lacked the pedigree of the university scientists who sponsored his work. According to Bliss, the local newspapers and the public were so taken with the idea of a shy, unpolished farmer boy making a breakthrough discovery that no one bothered to verify the details. It wasn’t long before Banting became a media darling across the world, eventually earning a Nobel prize for his work.

Bliss may be right that Banting has received more credit than he is due. But contrary to what the documentary suggests, this isn’t the real “myth” behind the discovery of insulin. The more pervasive and perilous fabrication is the idea that insulin was and is a “miracle” cure. At the beginning of the film, the voiceover narrates that insulin’s story is one “of two underdogs who came out of nowhere and cured one of the world’s most dreadful diseases.”

At this moment in the documentary, my seven-year-old with Type 1 diabetes looked up from her coloring book and said, “Insulin’s not a cure! It’s just a medicine!” Of course, she right; insulin therapy is merely a treatment. It does not and cannot reverse the disease for those with Type 1.

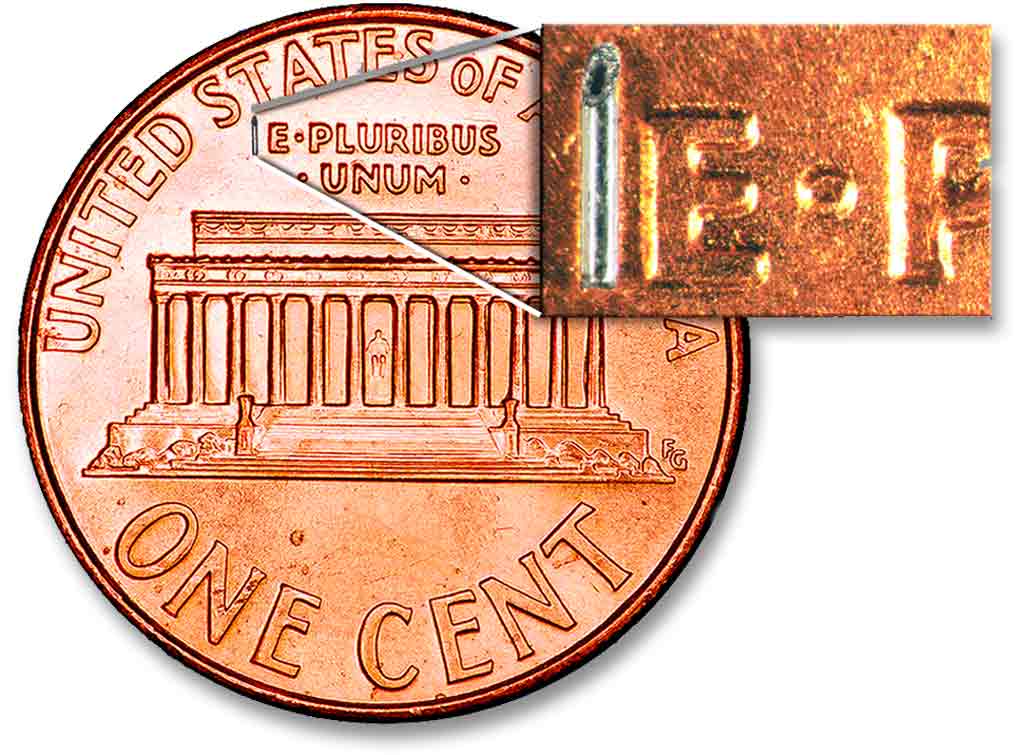

Unfortunately, calling insulin a “cure” was not the only incidence of mistake in the documentary. Like many historical accounts of insulin’s discovery, the film sensationalizes images of patients before and after insulin. These images show emaciated figures who are on the brink of death—and then, their fleshed out bodies, as they are brought back to life. This is powerful visual rhetoric, especially since it is coupled with poignant background music. (No joke: it sounds like a church choir singing to the angels while these images are reeling.)

These “before” and “after” visuals of insulin’s patients were widely promoted by the popular press and clinical circles in the years after Banting/Collip/whoever’s discovery. They complemented triumphant claims like this one from the New York Times: “one by one the implacable enemies of man, the diseases which seek his destruction, are overcome by science. Diabetes is the latest to succumb.”

Problematically, such hyperbole obscures the clinical reality of the disease. Slate’s documentary did not show that many of the patients pictured went on to experience miscarriages, blindness, organ failure, amputations, and other serious complications. Even today, with better treatment and technology, persons with Type 1 diabetes suffer significant complications. Another one of my family members, who has been living with the disease for over thirty years, is in the advanced stages of kidney disease. Yet, the public fails to realize the physical, psychological, and financial tolls that diabetes exacts.

This is, in part, because the “miracle” narrative of insulin has persisted since the 1920s. Slate’s documentary is not the only recent example of this storyline. In Great Britain, two filmmakers are working on a movie about the same moment in history under the working title, “Unspeakably Wonderful.” These were the exact words of Elizabeth Hughes, one of Banting’s first patients, to describe insulin therapy. It’s worth noting that Hughes, who happens to be one of the subjects of my own novel-in-progress, spoke these words within the first weeks of being treated, long before she realized that insulin would not, after all, eradicate the disease. Eventually, she and fellow patients would learn the sobering truth: that insulin merely transformed diabetes from a fatal to a chronic condition.

Now, of course, I realize that insulin is wonderful insofar as it saves lives. I realize that my child and many others would not be alive today were it not for the drug. And I think we should celebrate this feat—and also advocate for greater access and affordability so that all can benefit from insulin therapy. But we should not exaggerate insulin’s impact. Because when we overstate the wondrous effects of insulin, we trivialize the wounds of those living with the disease, while also diverting attention from the strength and grit that these individuals exhibit everyday.

Do you have an idea you would like to write about for Insulin Nation? Send your pitch to submissions@insulinnation.com.

Thanks for reading this Insulin Nation article. Want more Type 1 news? Subscribe here.

Have Type 2 diabetes or know someone who does? Try Type 2 Nation, our sister publication.