Frequent bacterial infections and coronary heart disease are both common complications suffered by those living with type 1 diabetes. The relationship between these conditions has traditionally been understood to be a matter of two separate conditions caused by elevated and fluctuating blood sugars.

But a new study out of Finland has found a connection between antibiotic use, high blood bacterial lipopolysaccharides levels, and heart disease that appears to indicate that bacterial infections may be a direct cause of coronary heart disease in people with type 1 diabetes.

How Bacterial Infections Damage the Heart

All type 1’s are at an increased risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD), with coronary heart disease (CHD) being the most common type of CVD.

The largest contributor to CHD and CVD, in general, is atherosclerosis which occurs when plaque builds up in the arteries and restricts blood flow. Hardening and inflammation of arteries can expedite this process.

Bacterial infections are known to induce inflammation and are thought to contribute to atherosclerosis by:

- Direct infection of vascular cells

- Indirectly inducing the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and proteins which flow through arteries

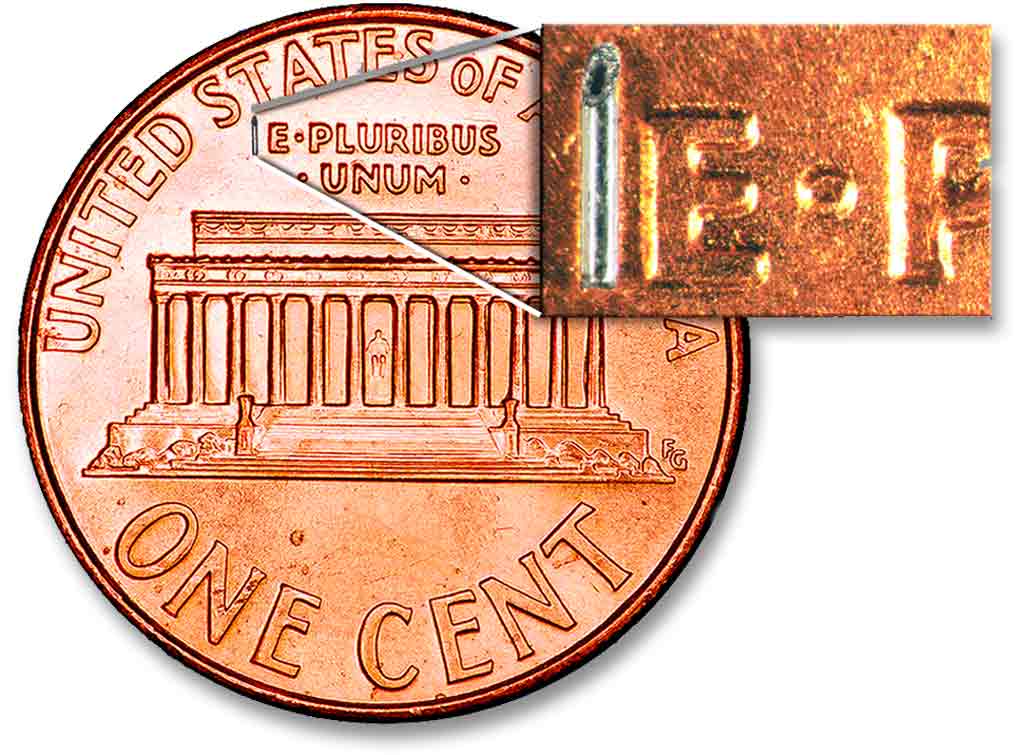

It has also been found that bacterial infections can trigger certain acute coronary syndromes. Previous studies have confirmed that bacterial lipopolysaccharides (LPS) — large molecules derived from the outer layer of certain types of bacteria — can increase CVD risk in an otherwise healthy person.

Unfortunately, the connection between bacterial infections and heart damage remains unclear, especially in the type 1 population.

- Previous studies have contradictory findings on whether or not the inflammation caused by infections actually contributes to worsening atherosclerosis or if it just happens to be present under those circumstances.

- Additionally, randomized trials using prophylactic antibiotic treatments failed to show a decrease in CHD risk.

For people with type 1 diabetes, specifically, there simply has not been much research into the subject.

At least, until now.

Frequent Infections Increase CHD Event Risk

According to the new Finnish study, which was published in the Journal of Internal Medicine, bacterial infections do appear to be a strong independent risk factor for CHD in people with type 1 diabetes.

By analyzing data from the Finnish Diabetic Nephropathy Study (FinnDiane), the researchers were able to compare antibiotic use, blood bacterial LPS levels, and incidence of CHD in adults living with type 1.

When comparing antibiotic usage, the researchers found:

- People prescribed, on average, one or more antibiotic per year had a 1.8 times greater chance of suffering a CHD incident than those prescribed an average of less than one per year

- The subjects’ risk for a CHD incident increased by 21% for each antibiotic they were prescribed per year

- Antibiotic usage increased within the two years before a CHD incident for those who experienced them

When looking at LPS levels exclusively, the researchers found:

- Individuals with high LPS activity had a cumulative incidence of CHD of 11.1%

- While low LPS activity individuals had a cumulative incidence of only 8.1%

When these two statistics were combined, those subjects with high antibiotic use and high LPS activity had the highest incidence of CHD at 13.6%.

Antibiotics or Bacteria?

While both high antibiotic use and high LPS levels were associated with higher CHD risk, it is still unclear as to how antibiotic use truly fits into the picture.

The researchers chose to look at antibiotic use as a way to track how often each subject was experiencing bacterial infections. However, some of the data appear to indicate that the antibiotics themselves may have been contributing to CHD incidents.

When looking at the combined effect of LPS levels and antibiotic use:

- Subjects that used a high number of antibiotics but had low LPS activity levels had a high cumulative CHD risk (10%);

- While subjects with low antibiotic use but high LPS activity levels had a relatively low risk (8.7%).

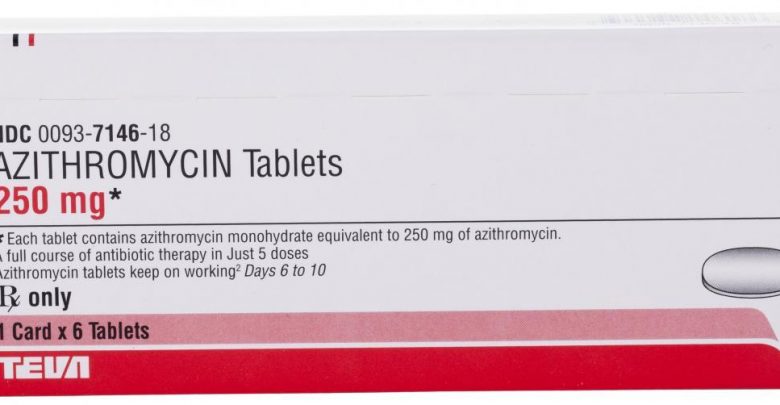

Even more interesting, the researchers found that subjects who experienced CHD incidents were prescribed fluoroquinolone-type antibiotics at a rate of 15.4% while those without CHD were only prescribed them at a rate of 7.7%.

Fluoroquinolones are known to increase a person’s risk of cardiovascular death through arrhythmia and aortic aneurysm and dissection. In people with diabetes, these types of antibiotics are also known to cause hyperglycemia and dangerous blood sugar fluctuations.

This effect alone could be enough to cause additional damage to the vascular system and thus increase CHD risk in people with diabetes.

The subjects without CHD were also found to be prescribed narrow-spectrum antibiotics at a higher rate (30.8%) than those that did suffer a CHD incident (22%).

Antibiotics of any kind can have negative effects on the user’s gut biome, but broad-spectrum antibiotics are especially dangerous for these good bacteria.

Previous studies have linked a healthy probiotic load to everything from decreased insulin resistance to a reduced risk of developing type 1 diabetes. Meaning there is a high potential that antibiotic use could further hinder a person’s ability to metabolize glucose. This could easily lead to higher blood sugars and more vascular damage.

Overall, this Finnish study confirms what many had already suspected: that an increase in bacterial infections corresponds to an increased risk of coronary heart disease.

But more research is needed on how antibiotics affect the heart health of people with type 1 diabetes to determine whether the damage is caused by the infections the antibiotics help treat or the antibiotics themselves.