Is the Public’s Lack of Empathy to Blame for Increased Insulin Costs?

How exactly did insulin become unaffordable? This is the question that Drew Pendergrass explores in a widely read piece for Harvard Political Review, which was published on January 22, 2018. Pendergrass begins by telling the story of Alec Raeshawn Smith, who recently died after an all-too-common practice: rationing insulin due to expense. Pendergrass then explores the sinister practices that have led to situations like Smith’s. For instance, he discusses price fixing between the major manufacturers, the lack of generic options, and the “twisted accounting” of the rebate-driven drug pricing system.

It’s the last item that seems to have most excited the diabetes online community. This may be because Pendergrass does such an exceptional job of unpacking such a convoluted scheme. In short, he explains how Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) and insurers pocket drug rebates from manufacturers that should be issued to patients. The tight-knit relationship between manufacturers, PBMs, and insurers negatively impacts all patients, but it has been especially detrimental for individuals with diabetes. There are a few reasons for this: these individuals need insulin to live, the drug costs are extraordinarily inflated, and there are no generic options.

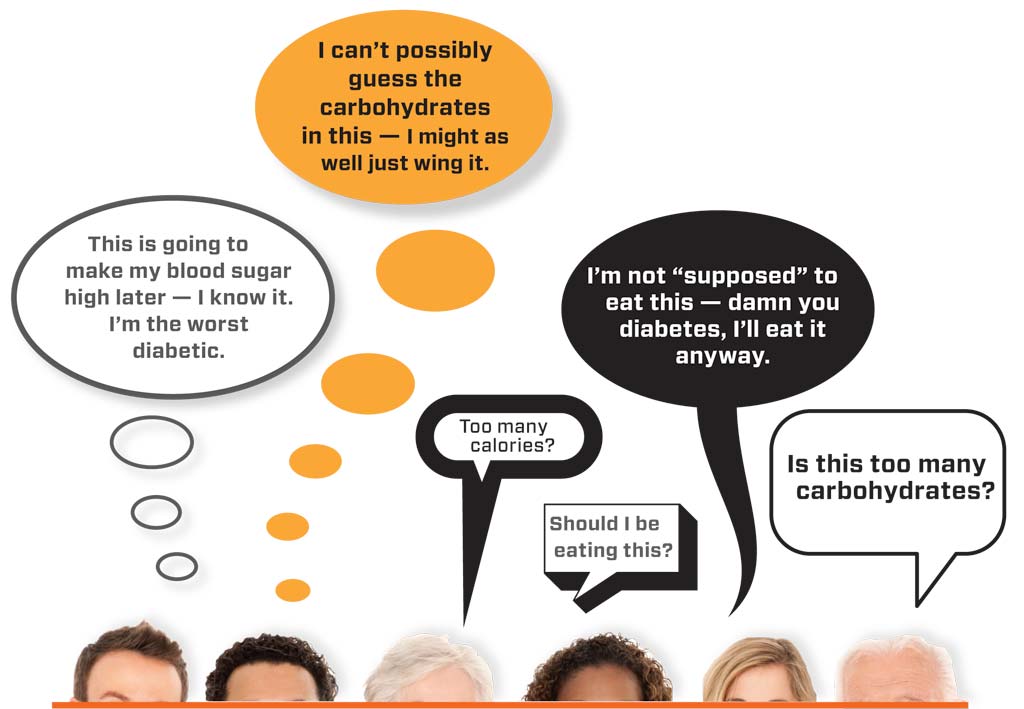

This perverted pricing scheme is definitely deserving of attention from those within and beyond the diabetes community. But Pendergrass makes another related point about which we should be talking—the public’s lack of empathy towards chronic illness, which has allowed for such injustices to occur in the first place.

Pendergrass argues that the public has turned a blind eye to the insulin cost crisis because the “industry has been successfully able to blame people with diabetes for high drug prices.” If only people ate right and exercised, drug prices would be lower, industry representatives claim. Of course, as Pendergrass notes, this rationale is problematic for numerous reasons. Besides being erroneous with respect to Type 1 diabetes (and many incidents of Type 2), this narrative “conveniently report[s] list price expenses, not the actual rebated cost to insurers. With this rhetorical flourish, attention is taken away from healthcare corporations and redirected towards patients themselves.” Yet, the public seems to have accepted the industry’s rationale.

Pendergrass then engages two diabetes advocates about this issue: Peg Abernathy and Julia Boss, both of whom support his argument that there is a “culture of contempt” in America towards long-term health problems. Boss writes, “Americans tend to treat sudden catastrophic health crises (heart attack, cancer) as a matter of bad luck, but chronic conditions like diabetes as a matter of bad choices.” Abernathy adds that such contempt is not exhibited towards other chronic conditions, such as allergies, which are not perceived to be lifestyle-related. Case in point? A few years ago, the public was outraged when the costs of EpiPens increased exponentially. But no one seems to care that insulin prices have increased 700% in the last 20 years.

Insulin Nation had the opportunity to further discuss the empathy issue with Abernathy. To start, we asked her to elaborate on the causes of this culture of contempt toward chronic illnesses like diabetes. After all, don’t a lot of Americans have long-term health issues? She responded by citing the generalization of diabetes as the first problem.

“With Type 1 diabetes and Type 2 diabetes, there is often a tendency to lump the two together and blame patients for poor lifestyle choices, which is never the case for type 1 diabetes . . . and not necessarily the only causal effect for developing [Type 2] condition.” From her perspective, we need to differentiate between the types, just as we do with other conditions. “Think of heart disease. They share symptoms and complications, but the various types of heart disease are treated quite differently. For example, you wouldn’t put a person on cholesterol medication if their only issue was a hole in the heart.”

Read Dear Media: The Way You Talk About Diabetes is Problematic

Is the media is to blame for perpetuating misinformation and contempt, by extension? In part, yes, says Abernathy. It is “sloppy reporting” to use the standalone term “diabetes,” as there are few instances in which it is appropriate. She cites the frequency of media stories about diet and exercise in connection with diabetes, which misreport the reality for individuals with Type 1 diabetes like herself. “No matter what we eat, how much we weigh or what our exercise level is, until there is a cure, we will always be dependent on insulin for our lives.”

Another problem? The media “misses the opportunity to add that certain life and death detail into the mix.” Because of the conflating of the types, the public does not understand that insulin is, in many cases, necessary for survival. “We need to EpiPen insulin,” says Abernathy. By this, she means that advocates need to educate the public about the dire need for the drug, just as advocates did on behalf of EpiPen users. “With the EpiPen, it was easier for [advocates] to present a compelling story as it has a singular outcome, saving the lives of people (and many kids) who are at risk by going into anaphylaxis shock.” Not surprisingly, the public and legislators quickly got behind this narrative. In order for lawmakers and the general population to similarly support the diabetes community, they must understand the essentiality of insulin.

To make this case, it’s imperative to acknowledge the social and geographical reach of the disease. “The type 1 tentacles reach far and wide, sparing no culture, country, economic status, gender, age or race.” Across the world, some face more difficulty in terms of access and affordability than others. But all individuals with Type 1 face this same reality: “Without insulin, we die. We. Die. We do not live.”

So, what can individuals do to advocate? For many, it’s difficult to take on tasks on top of managing diabetes and professional responsibilities. “Keep it simple,” Abernathy advises. “Grassroots advocacy can begin by never saying ‘diabetes’ when speaking about your type 1 or type 2. Just start there. Differentiate, educate, and help people understand that for us, insulin is a matter of life and death.” She herself routinely looks for such “teaching moments” in her daily life. If her condition comes up in conversation, she makes sure to clarify, “I have type 1 diabetes. You know. The kind where I need insulin in order to survive?” This fact alone (the dire necessity of insulin) “has the potential to begin a change in attitude and thus, empathy.”

Do you have an idea you would like to write about for Insulin Nation? Send your pitch to submissions@insulinnation.com.

Thanks for reading this Insulin Nation article. Want more Type 1 news? Subscribe here.

Have Type 2 diabetes or know someone who does? Try Type 2 Nation, our sister publication.