How Diabetes is Both Invisible and Sensational

In the digital age, images matter. A writer can produce a well-researched and exquisitely written story, but without an accompanying photograph, no one is going to be interested in publishing or reading it.

A story about a collapsed bridge will, of course, include a picture of the collapsed bridge. A story about a cancer-victim will most likely include a picture in which the subject is visibly ill, as evidenced by a lack of hair or a hospital setting. Images help a reader to visualise the scene, and they also prove that the story is credible.

But some diseases, such as diabetes, are just not sexy. At least not to the media. There is no obvious side effect that would perfectly illustrate an article about diabetes–our skin does not blister with scars or boils. We don’t lose our hair, and we don’t stand with a stooping gait.

I have lived functionally and happily with Type 1 diabetes since my diagnosis 18 years ago. I look entirely normal to 95% of the people I come across in my daily life–the commuters I sit next to on a busy train, the shop assistant with whom I chat as I pay for my newspapers. These individuals will never know that I prick my fingers multiple times every day to measure my blood sugar or that I have an uncanny knack at knowing the carbohydrate content of everything I eat–not because I want to, but because I must to stay alive.

This is a blessing and a curse. It enables me to function as an ordinary adult. However, it also means that I rarely see an accurate representation of what I know my condition to be. Too often, the media uses diabetes as a cautionary tale to warn against unhealthy lifestyles. Never mind that Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune illness that affects an estimated 40 million people globally. This single storyline has real consequences. Growing up, I felt rare and unlucky– an anomaly in a society of people who are mostly healthy.

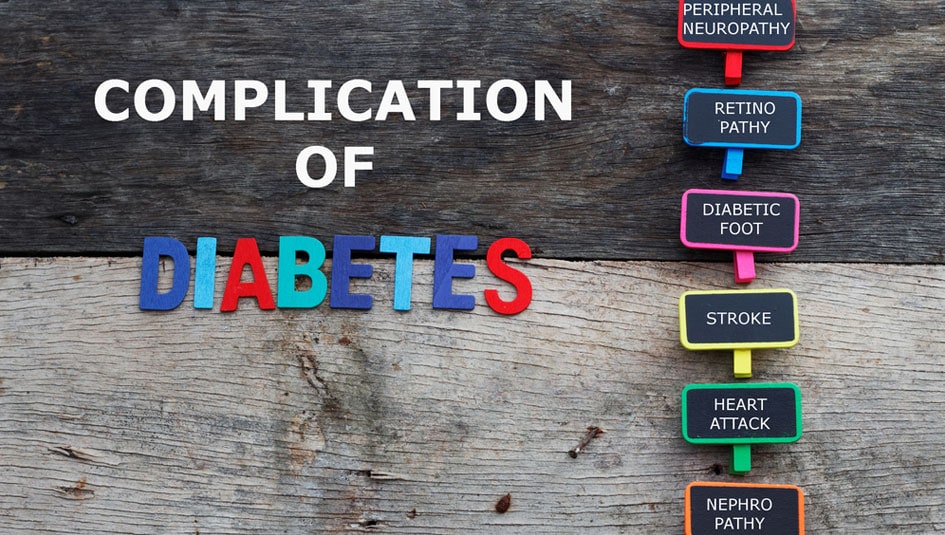

Newspapers and media outlets both in America and around the world are packed with articles advising which foods to avoid to prevent a diabetes diagnosis, the very real problem of skyrocketing insulin prices, and sensationalised stories about people’s untimely deaths due to complications of poorly controlled diabetes.

While these articles pursue important topics, they too often conflate the subtle differences of treating and diagnosing the five types of diabetes. They feed the ignorant public view that there is just one generic type of diabetes that can be caused due to a one-off event (eating too much sugar). They present diabetes as a medical condition that is easily treatable if you stick within the numbers advised by your glucose meter. They rarely venture into the real-life sacrifices and struggles faced by the diabetic community.

Diabetes is an emotional disease as much as it is a physical one. No media outlet dares to talk about diabetic denial or diabulimia or how terrifying it can be to come around from a hallucinatory hypoglycaemia. The physical pain of missed injections is never talked about. The connections between stress, grief, hot weather, and the havoc these can play on blood sugar are never recognised.

In this respect, diabetes is very much an invisible illness. Beyond the serious complications such as amputation and the few moments a day in which we stick an insulin injection into our legs, it would be easy to believe someone living with diabetes every day, in fact, isn’t.

As a journalist, I know that if I sensationalised the dramatic hypoglycaemia I had at the Acropolis in Athens, Greece, it would sell. (I temporarily lost my vision and my ability to eat, and I ended up vomiting into a bin in front of a crowd of tourists.) Combined with a quote from my mother who was desperately trying to assist me at the time, the papers would snap it up. Illustrating such an article would be easy– a family photo of the Acropolis temple and, hey presto, I’ve got myself a story!

If the publication outlet asked for a photo in which I am visibly diabetic, that would be more of a problem because I look like a normal person. I wear an insulin pump, but is that a dramatic enough photograph to summarise my condition?

Despite being a global epidemic, diabetes is much more useful to the media when it can be sensationalized. The media applies the risk of diabetes to everyone’s lives, rather than discussing the impact of diabetes on the lives of the 6% of the world who live with some form of it.

Educating the public is important, but representation for those living with the condition is even more crucial. A child dreams of becoming an athlete because they see an athlete succeeding on television. Someone living with diabetes can feel less alone if they see accurate representations of the highs and lows of their condition in the media.

Perhaps if these representations existed, a newly diagnosed child now would never have to feel like an anomaly in a healthy world.

Do you have an idea you would like to write about for Insulin Nation? Send your pitch to submissions@insulinnation.com.

Thanks for reading this Insulin Nation article. Want more Type 1 news? Subscribe here.

Have Type 2 diabetes or know someone who does? Try Type 2 Nation, our sister publication.