Faster Insulin: Short and Sweet

One of the necessary ingredients of an artificial pancreas is faster absorption of rapid-onset bolus insulin. Today’s ‘fast’ insulins reach their peak blood levels in 60 minutes after injection or infusion bolus, and it takes another 20 to 30 minutes to achieve their maximum glucose-lowering effect. That’s quite a contrast to insulin secreted by a normally functioning human pancreas, which deploys the hormone into the bloodstream within five to 10 minutes of your first bite.

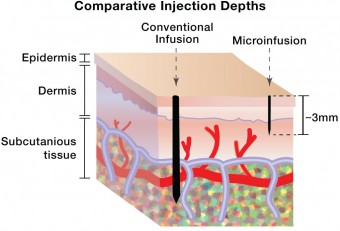

The search for faster insulin absorption centers on two broad areas of research. One focuses on figuring out how to produce a stable supply of insulin monomers, the ‘active ingredient’ in insulin that allows it to control and direct glucose. The other seeks to speed up absorption by changing the injection device and technique so that insulin is delivered in a way that will disperse it faster. Intradermal injection or infusion — which dispenses insulin into the first layers of the skin — is one of the methods that is being explored as a means of delivering the insulin more quickly. Today, intradermal shots help identify allergies, treat rabies, or test for exposure to illnesses such as tuberculosis. Tomorrow, they may be used to inject insulin, getting it where it needs to go about 40 percent faster than the subcutaneous method.

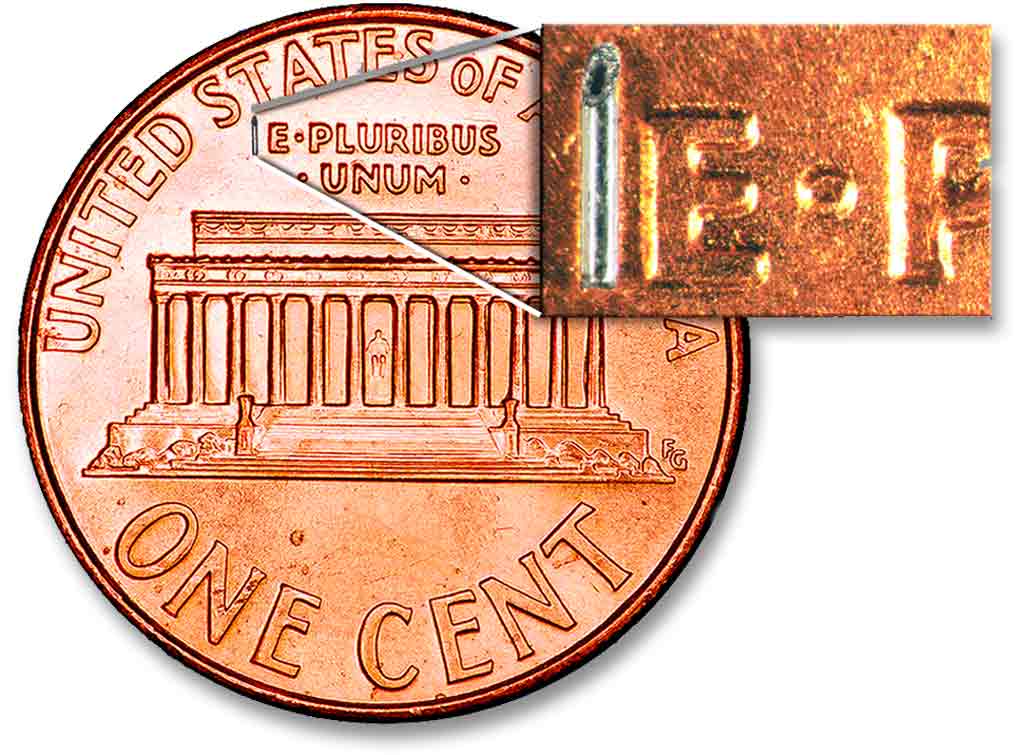

The primary research into intradermal insulin injections is being done at Becton Dickinson (BD), a global medical technology company. In fact, Insulin injections and BD are so entwined that it is hard to imagine one without the other. In 1924, BD made the first glass syringe specifically designed to inject insulin, and today the company continues to be the dominant provider of needles and catheters used to inject and infuse insulin and many other medications and vaccines. The company’s innovations have been plentiful over its 116-year history, but theirs is not a research process that rushes products out the door. BD’s next major diabetes-oriented launch, a 1.5 mm micro-needle only a little larger than the thickness of a human hair, is most likely a few years away. Given BD’s track record, it will probably be worth the wait.

First, Some Facts About Skin

How do we know that super-short needles can actually deliver insulin to precisely the right place? Because BD’s research has shown that skin is skin. Several years ago, as part of the process of developing its 4mm Nano needle, the company conducted the largest analysis ever of the differences in human skin thickness at insulin injection sites. Their conclusion: human skin thickness falls within a very confined range. In fact, the skin thickness of a 300-pound middle-aged truck driver and a petite twenty-something woman are not that different.The range of skin thickness is roughly 1.25 to about 3.25 millimeters and it averages 2 to 2.5 millimeters. It does not vary by clinically important amounts related to age, gender, body mass index, or race. Therefore, a 1.5 mm needle will hit the target squarely in nearly all patients.

Why Millimeters Matter

It’s only 2.5 mm, but differences between absorption of insulin injected subcutaneously through the existing 4mm BD Nano pen needle and the 1.5 mm micro-needle now being tested are quite significant. BD’s Worldwide VP of Medical Affairs for the Diabetes Unit, Dr. Larry Hirsch, explained the intradermal effect as follows: “You get faster uptake of the insulin when it’s given intradermally versus subcutaneously. If you visualize an absorption curve, you see a shift to the left. Intradermal insulin is taken up faster, it goes to a slightly higher peak level, and the levels decline faster than when you give it subcutaneously. The total amount delivered is the same, however.” In other words, intradermally delivered insulin tends to act more like insulin delivered by a normal pancreas, in which the hormone arrives faster and declines faster than is the case with subcutaneous injections.

Pens and Pumps

“We initially started working on injection systems using micro-needles to inject insulin into intradermal space four to five years ago,” said Maggie Taylor, director of research and development in BD’s Diabetes Care unit. “We’ve done a number of clinical trials to show that it’s feasible, and to show the effects of insulin when it’s injected into the intradermal layer. In the last couple of years we’ve collaborated with JDRF on a micro-needle infusion set for pump patients. We call it micro-insulin infusion, and we’ve completed a couple of clinical trials to show proof of concept.”

Taylor went on to say that the basics of pump-based infusion will not change with the introduction of micro-needles. As is the case with pen injections using the same shorter needle, what does change, in the clinical trials to date, are the kinetics of the insulin being dispersed.

“Most people tend to look at the time that it takes to get insulin to the peak level in the blood,” Hirsch said. “This is called “T-max”™ – time to maximum insulin level – and that parameter is accelerated roughly 40 percent when you give insulin intradermally versus subcutaneously. So, if you expect a “T-max”™ with Humalog, Novolog, or Apidra, of roughly an hour, you see a “T-max”™ in the range of 35 to 40 minutes when you give it intradermally. If you’re talking regular insulin, “T-max”™ is usually 120 to 140 minutes after injection subcutaneously, and that gets reduced to about an hour. There is some variability, but the results are consistent.”

The Long and Winding Road

Despite the promising results of clinical trials so far, don’t expect to see micro-needles in either pens or infusion sets until later in this decade. Like most professionals involved with trials for new drugs or new devices, Dr. Hirsch is reluctant to name a specific on-the-market date. What is known is that successful results from trials of a super-short pen needle don’t carry over to potential approval of a micro-needle pump infusion set. Each application requires a completely separate set of tests. “We have to validate that the devices work as intended, and that they work well with available pens and insulin pumps,” Hirsch said. “We have to demonstrate that insulin given this way is ‘safe and effective’ to regulatory authorities. This requires major clinical trials that have to go through greater and greater levels of complexity and duration. It takes a lot of time and a lot of resources.”

Caution aside, both Hirsch and Taylor light up when they talk about patient reactions to the micro-needle in the trials. “Most patients say that they feel practically nothing when this type of needle is inserted in the skin,” Hirsch reported. “They say it’s almost imperceptible.”

“It’s not just the lack of pain, it’s the perception,” Taylor added. “They can’t even see the needle, so the emotional reaction to the needle goes away. It’s like they’re not even using a needle at all. I think it’s very powerful.”

Amen to that, and let’s keep those trials moving.