After 35 Years of Dead Ends, Ohio Researcher Develops Heat-Resistant Insulin

Good things come to those who persist. After thirty-five years of studying the drug, Michael Weiss and his team have developed heat-resistant insulin. (Weiss recently became Chair of the Department of Biochemistry & Molecular Biology at the Indiana University School of Medicine; however, it was his research at his previous institution, Case Western University, which led to this promising discovery.) Heat-resistant insulin could benefit insulin-dependent individuals across the world, since it creates greater flexibility for storing and travelling with the medication.

Weiss has seen first-hand how hard it is for some individuals to keep insulin at safe levels. As a graduate student, he travelled to less developed countries in Africa, where electricity is unreliable or non-existent. In these nations, he noted, it was common for individuals to bury insulin and other temperature-controlled medications in the ground in order to prevent degradation. Since many of these countries are close the equator, temperatures are significantly more elevated. This reality, coupled with less developed industry and architecture, makes safe insulin storage very difficult.

Even in more affluent countries like the United States, preserving insulin can be strenuous. Weather-related power outages can impact home refrigeration. And during the summer, it’s hard to take insulin on the go, since the drug cannot be left in a vehicle or exposed to extreme temperatures.

After his trip to Africa, Weiss devoted himself to identifying a heat-resistant type of insulin. He anticipated that such a project could be completed in a few months’ time. Instead, it took him three and half decades. But he’s happy to say, “We finally think we do have a solution.”

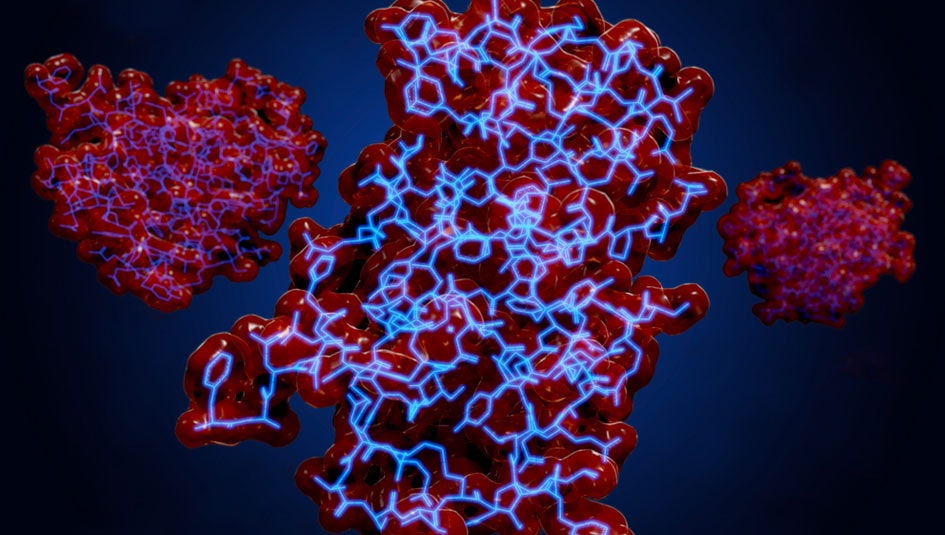

For Weiss, insulin is a “beautiful molecule.” (In fact, he loves his subject so much that he has an artistic image of insulin in his research office.) He is intimately familiar with insulin’s chemical personality. As he explains, insulin is a protein. As such, it consists of a sequence of amino acids. These acids are like building blocks that give the molecule a certain shape at which it performs. By using a special machine to determine the point at which insulin unfolds, Weiss compared different analogs.

“When you get to know a molecule atom by atom, you can have an intuition for what changes you can make which would alter properties that might be more favorable for patients,” Weiss told another news outlet. He studied how insulin works in other creatures and found that birds’ produce and use insulin in a part of the molecule known as the A-chain. This position was less than optimal in human insulin. He combined this knowledge with data gathered from worms to create an “ultra-stable insulin.” In his words, “We found a sweet spot.”

Weiss’ career began with a generous JDRF Career Development Award. He told Insulin Nation, “JDRF has been a key part of my scientific life and social interactions in the T1D community for almost 30 years.” His latest research was funded by French pharmaceutical giant Sanofi, which gave $17 million in seed funding. He is very confident about the impact of his findings on future research and treatment. He is especially enthusiastic about the possibility of using the fast-acting formulation in upcoming generations of implantable insulin pumps, which will ideally be connected to a continuous glucose monitor.

Why is it so critical for the closed-loop system to use heat-resistant insulin? When we asked about this, Weiss explained that when insulin is stored in a reservoir at body temperature for a three-month period, it is “too often aggregated or [can] form amyloid that occludes the catheters.” He adds that the new insulins are “ideally suited for closed-loop systems because the extensive peritoneal membrane permits ultra-rapid absorption, which helps the safety and efficacy of the control algorithms connected to the CGM and pump.”

What’s next? Well, Weiss’ team has a research partnership with a major pharmacy firm to support work for clinical trials. But the team first has to select the best critical analog. He explains, “clinical trials are expensive, and so we wish to make sure that the final candidate analog is the best we can design. We expect a decision within 6-12 months.” This will lead an an Investigational New Drug (IND) application to the FDA and then to “Phase 1” human trials.

Weiss also has cold-resistant insulin on his radar. “This will be one of our next papers,” he says. “We hypothesize that a subset of the physico-chemical strategies that confer heat resistance will also confer resistance to denaturation through repeated freeze thaw cycles.”

Do you have an idea you would like to write about for Insulin Nation? Send your pitch to submissions@insulinnation.com.

Thanks for reading this Insulin Nation article. Want more Type 1 news? Subscribe here.

Have Type 2 diabetes or know someone who does? Try Type 2 Nation, our sister publication.