A New Paradigm for Type 1 Diabetes Origin

Beta Cells become pro-inflammatory before immune response; leading to new path for type 1 diabetes diagnosis/prevention

We spoke with Ajit Shah, PhD and Peter Thompson, PhD about their research which has just been published in Cell Metabolism.

This UC San Francisco study of human and mouse pancreatic tissue suggests a new origin story for type 1 diabetes (T1D). The findings flip current assumptions about the causes of the disease on their head and demonstrate a promising new preventative strategy that dramatically reduced disease risk in laboratory animals.

In their Cell Metabolism article, lead authors Peter Thompson and Ajit Shah show that pancreatic beta cells themselves may play a much more active role in T1D than previously appreciated, opening the door to a totally new avenue for therapy.

Dr. Anil Bhushan’s laboratory focuses on cell cycle regulation and epigenetic changes that regulate pancreatic beta cell formation and regeneration. Dr. Bhusham, who has long studied the biology of pancreatic beta cells, said that he has never been completely satisfied with the dominant model of the origins of type 1 diabetes.

“Why does the immune system attack just those cells, while leaving neighboring cells of other types untouched” questioned Dr. Anil Bhushan

Findings sharply contrast with belief that T1D is caused by an overly aggressive immune system

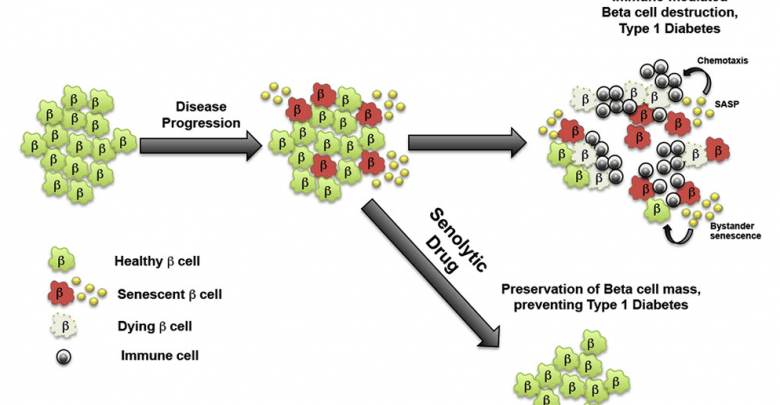

The new data suggest that rather than an overly aggressive immune system, it is inherent problems with DNA repair in some beta cells that triggers senescence, which patrolling immune cells first fail to recognize and clear out. As a result, these problem cells accumulate and spread so widely within the pancreas that by the time the immune system eventually recognizes the problem, it essentially has to raze the whole insulin-producing system, leading to the onset of diabetes.

Confirmation in Humans

To determine whether beta cell senescence plays a role in the onset of T1 diabetes in humans, the researchers studied pancreas tissue from deceased donors, sourced from the Network for Pancreatic Organ Donors with Diabetes, based at the University of Florida. This access was provided by Mark Atkinson, a co-author, who works at the UF Diabetes Institute in, Gainesville, FL

We selected a cohort of adolescent and young adult (ages 12-28) nondiabetic, autoantibody-positive and T1D donors (6 donors per group). Males and females were present in each group. We also chose the same number of donors from similar ancestries (including European, Asian, African) in each group. The T1D donors were all fairly recent onset (from 1-5 years with T1D) and some of them were juvenile cases (Ages 12-14). Autoantibodies included IA-2, GAD65, Insulin, and ZNT8. BMIs were all within the normal range.

In line with their animal findings, the authors identified clear signs of DNA damage and secretory senescence in the beta cells of six donors with early-stage T1 diabetes, compared to six non-diabetic donors. The researchers also found signs of beta cell senescence in six donors without a diabetes diagnosis, but whose blood showed early signs of an immune reaction against beta cells, corroborating the idea that senescence is an early part of the chain of events leading to the disease.

“Seeing this data was an incredible moment,” said Thompson. “Many results from these diabetic mouse lines have not panned out in humans, but the fact that we were seeing the very same markers of senescence in human pancreas tissue indicated that the same process is occurring in the human disease as well.”

New Therapy Option

To test whether eliminating senescent beta cells could help prevent T1 diabetes, Bhushan’s group tested a drug called ABT-199 (Venetoclax), recently approved by the FDA in 2015 as a second-line chemotherapy agent for a type of leukemia that also acts as a so-called senolytic — a drug that selectively eradicates senescent cells.

Remarkably, the researchers found that while 75 percent of control mice developed diabetes by 28 weeks of age, only 30 percent of mice who were given ABT-199 for two weeks prior to the onset of symptoms went on to develop the disease. The researchers showed that the drug had rapidly eliminated senescent beta cells in these mice, after which their immune systems (which were not directly affected by the treatment) left the remaining, healthy beta cells alone, avoiding the loss of insulin production that causes diabetes.

“These findings support the idea that senescent beta cells are like the bad apples that spoil the whole basket,” Shah said. “Here we show that eliminating the bad apples can save the rest, which brings a new therapeutic avenue for treating patients with T1 diabetes.”

Next Steps

“In order to translate our findings, we need to develop a test that will reliably identify beta-cell senescence in a noninvasive way in people. We anticipate some biomarker will be an early warning indicator. Once we can link senescent beta cell accumulation with other risk factors for T1D, such as family history and/or autoantibodies, we would then be in a position to set up a clinical trial to evaluate Venetoclax therapy for preventing T1D in those who are at highest risk. Venetoclax or other related drugs that clear out senescent cells could also have therapeutic benefits for those with recent onset or established T1D, but more work is needed to better understand the effect of senescent beta cells on healthy beta cells in that context.”