3 Ways to be there for Your T1D Child

After our son was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes, I attended a series of diabetes education sessions. During one, a nurse mentioned that each parent should expect a breakdown from their child. She quickly moved on to other topics, and I was left to wonder what that meant. The hospital sent me home with a diabetes book that had sections on blood sugar management, sliding scale corrections, and diet advice, but little on emotional support.

Nothing prepared me for the breakdown when it came on suddenly one morning as we pulled into school. It started with my son looking at me with tears in his eyes and asking, “Why me?” I had no answer.

I soon learned that diabetes means that he is different and I need to learn how to support him as he learns to be ok with being different. Here are three lessons I’ve learned during that journey:

Sometimes it’s ok to say “I don’t know.”

When my son hit his first T1D brick wall and asked “Why me?”, I wanted to answer him. I quickly realized that I had to be straightforward and tell him that I didn’t know why this happened and I couldn’t make it go away. My job was to listen, because there was no answer and I had to be comfortable with that. The best thing I could do was help him work through it and, if he didn’t want to talk to me, I needed to find someone else for him.

Empowering him is more important than watching over him.

Who would have thought that my 9-year-old son would know more about taking care of his diabetes than 99 percent of the adults around him? Recently, my son was at a birthday party where, despite my telling the host that “he can eat anything,” the adults selectively decided to restrict what he could eat in front of the other kids. I listened to how the situation made him feel and we brainstormed on how he could, when he was ready, take control by either calling or texting me to head off that situation in the future. While it is important to me that my child respects the adults around him, I also explained that he knows more about his body than anyone else, and that it is ok to politely tell an adult that their approach or suggestion is not the way he manages his diabetes. While I can’t educate everyone around him, I can equip him with a phrase or two to politely engage well-meaning adults so that he doesn’t have to feel so publically different.

He is going to feel “blue” about having diabetes, no matter what I do.

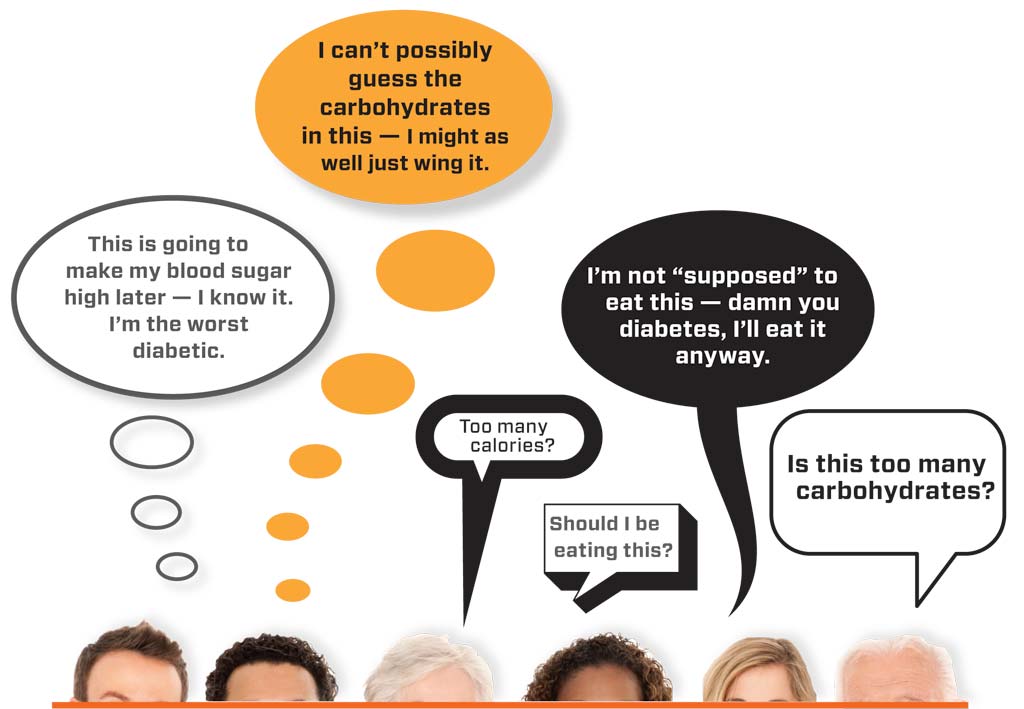

Most of my son’s classmates, teachers, and friends don’t live with a disease that they will have for the rest of their lives. This chronic intrusion into his childhood will make him feel depressed at times. I need to watch for those times and make sure the depression resolves itself, and help him troubleshoot obstacles to his happiness. Is he going to be upset or uncomfortable on his first date when he has to test in front of someone? Does he not want to play soccer anymore because the coach makes him check his blood sugar and he doesn’t want to be different? To me, success is helping him recognize and tell me when his diabetes is changing the way he does things. Then we can come up with a plan.

While diabetes doesn’t change the expectations I have of him, it does remind me that he is on a different path than most kids. The challenges he has as a fourth grader are going to be different than those he has as a high school junior, and I want to ensure that he has the life he wants and that he is prepared to take care of himself when I am no longer at his side. I want to know and I want him to know that he is prepared with the knowledge he needs to take care of himself physically and emotionally.