Inhalable Insulin — A Breathtaking Development

If AFREZZA finally wins FDA approval this year or early in 2014, Alfred Mann legitimately could be considered a strong runner-up candidate to Banting and Best as diabetes’ “Man of the Century.” Add ultra-fast inhalable insulin to developing the first mass-market insulin pump (MiniMed), the first continuous glucose monitor, and the broad framework for the artificial pancreas, and it might be hard to find anyone who contributed more to treating diabetes over the past century, other than the discoverers of insulin itself.

Will AFREZZA actually win approval? This time around, its third run through the FDA gauntlet, there are many positive signs. But, as Mann can tell you, that’s happened before, only to have approval vanish like a mirage in the desert. As two more (and hopefully final) sets of clinical trials approach conclusion, all that he, and his company, can do now is wait and hope.

The AFREZZA saga reads like a movie script. A brilliant innovator/CEO discovers a small company with technology that he thinks could revolutionize the development, use and absorption speed of man-made insulin. He sells his existing diabetes business to a giant conglomerate for billions and sets out to commercialize his new product, which didn’t fit with the conglomerate’s business model. He invests close to a billion dollars of his own money, suffers from the backlash of a pharma giant’s failed attempt to market what was considered to be a somewhat similar treatment approach, is denied FDA approval not once, but twice — the second time under somewhat mysterious circumstances — and and finally, wins approval for a therapy that would benefit millions of people with diabetes.

Hollywood might reject the storyline as unrealistic, which only goes to prove that truth is stranger than fiction, because this, in a nutshell, is the tale of Al Mann and AFREZZA.

Except for the approval part. That remains to be seen.

The Trouble With Hexamers

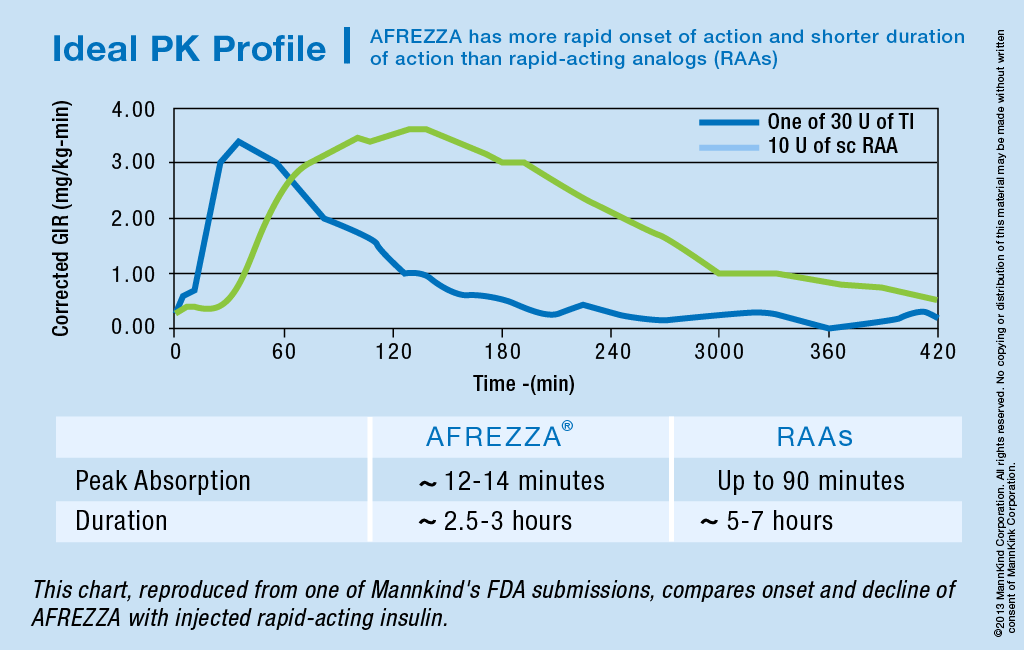

AFREZZA is a technology-cum-therapy that delivers bolus insulin for mealtime glycemic control. It combines a small inhaler with an aspirin-size caplet of insulin bonded to a fine, powdery substance that, when inhaled, makes man-made recombinant insulin act very much like the naturally produced counterpart. Mann believes his product will revolutionize insulin therapy for diabetes, because the molecular structure of the drug, and therefore its ultra-fast action, is both different from and superior to any existing, rapid-onset, injectable insulin product.

In people who do not have diabetes, insulin is stored in the body as a hexamer, a unit of six molecules. But only the insulin monomer, a single molecule, is active in helping the body to break down and use glucose as energy. Because natural insulin enters the bloodstream at lower concentrations and higher pH, the hexamer breaks down almost immediately when the body senses new glucose. Man-made, injected insulin mimics the hexamer structure of the natural hormone, but because it is injected into subcutaneous tissue, rather than directly into the bloodstream, it takes a relatively long time for the body to break down the hexamer. As a result, injected insulin does not respond to new glucose in the body nearly as quickly as its natural counterpart. As anyone who uses rapid-acting insulin knows, it takes about 60 to 90 minutes for injected rapid-onset insulin to reach its peak.

The dilemma is deceptively simple to describe: to make insulin that can be stored for weeks or months outside the body, the active ingredient must be placed in a structure that slows down absorption. Undergoing testing now are several therapies that increase absorption rates by as much as 40 to 60 percent, but nothing has even come close to the onset speed of natural insulin.

That is, until AFREZZA.

Finding (Another) Pot of Gold

The story begins almost 15 years ago, when Mann was still CEO of MiniMed. That company was then exploring the possibilities of using its diabetes pump technology to infuse other drugs into the body, and two of the drugs they were working with were not stable. MiniMed’s chief chemist at the time told Mann about a group he’d discovered that used a technology called Technosphere® to stabilize large molecules. MiniMed hired the company to test its technology on the substances in question, and both experiments were successful.

Then it dawned on Mann that this could also be a diabetes treatment breakthrough. “I wondered if this could help us make a stable form of insulin monomers,” he recalled. “I ordered a formulation with insulin monomers, and when I saw the trial data, I said, ‘My God, this will revolutionize diabetes!’” MiniMed acquired the small company and the rights to its technology.

Mann believes his product will revolutionize insulin therapy for diabetes, because the molecular structure of the drug, and therefore its ultra-fast action, is both different from and superior to any existing, rapid-onset, injectable insulin product.

In 2001, Medtronic purchased MiniMed and Medical Research Group, a closely held affiliated company in which Mann owned a major stake, for a combined total of almost $4.2 billion. Mann’s stake in the two companies was worth more than $1 billion, and that went into Mann’s pocket, although he gave almost half of the proceeds to charitable foundations. As a device company, Medtronic had no interest in venturing into drug development, so Mann and some other MiniMed stockholders set out on a new path, trying to take advantage of the rights to the Technosphere® technology, which had so excited him.

Mann was not a neophyte at starting and selling companies. He was already a billionaire from other successes. MiniMed was the tenth company he had launched and the sixth he had sold, including a heart pacemaker company that today forms the core of St. Jude Medical’s cardiac product line. At the age of 75, in 2001, he had no intention of retiring. Instead, he launched Mannkind Corporation, and went to work developing AFREZZA, along with several other products.

Gold Dust

The Technosphere® technology that captured Mann’s attention in the late ’90s essentially allows the active ingredients in certain drugs to bond to crystals of an inert powdery substance that can be inhaled. In AFREZZA, only the insulin monomer – rather than the insulin hexamer – is absorbed by the powder, allowing the inhaled active insulin molecules to begin working almost immediately, just as does insulin produced by a healthy pancreas. AFREZZA not only gets where it has to go quickly, but it is also absorbed far faster than injected insulin. In addition, because AFREZZA has a short “tail,” the potential of hypoglycemia caused by combining “left over” basal insulin with bolus insulin is dramatically reduced. “You’d have to try to become hypoglycemic using AFREZZA,” Mann said. His claim has been borne out in dozens of clinical trials of AFREZZA involving almost 6,000 patients since Mannkind began testing in 2006.

The Exubera Debacle

The Exubera Debacle

When it comes to proxies for spectacular and costly failures, it’s Ishtar in movies, Edsel in cars, and Exubera in prescription diabetes drugs. Using technology first developed by a small company called Nektar Technologies, pharmaceutical giant Pfizer began working on its inhaled insulin product in the late 1990s. Exubera was introduced in September 2006 and withdrawn from the market in October 2007, not because of safety concerns, but due to poor sales. Despite heavy promotion by Pfizer, Exubera captured less than one percent of the insulin market in the first nine months of 2007, generating a puny $12 million in sales. Pfizer wrote off $2.8 billion, including $661 million in Exubera inventory. And this is probably a conservative estimate of the true cost.

What went wrong? Just about everything possible. In the first place, Exubera’s powdered insulin used a different molecular structure than AFREZZA, and while its clinical trials showed that it worked almost as well as injected insulins, there was really no therapeutic advantage. Second, the product was significantly more expensive than injectable insulin, and the higher cost was not offset by superior results. A third problem was the size of the Exubera inhaler, which needed its own carrying case and was not something people would want to pull out in a restaurant. Finally, Pfizer pitched inhaling as an alternative to painful shots, which simply did not resonate with enough people, let alone with insurance companies that would have to pay higher amounts for the new therapy, to overcome the other obstacles.

Mann knew that Pfizer would be first to market with inhalable insulin, but hoped that Exubera would lay the groundwork for the therapy and that AFREZZA would benefit by getting Pfizer’s customers to switch. They didn’t expect Pfizer to throw in the towel as quickly as the company did on something that had cost so much to develop. Worse, the entire concept of inhaled insulin was thrown under the bus by Exubera’s failure. The fallout, says MannKind’s Chief Financial Officer Matt Pfeffer, “haunts us to this day.” Pfeffer, who at times plays the role of company spokesman, went on to say, “We almost downplay the whole inhalation aspect. That’s why you hear us referring to it as a new class of ultra-fast-acting insulin that really can mimic the kinetic curves of natural human insulin from a healthy pancreas.”

Dancing With The FDA

On March 16, 2009, Mannkind submitted to the FDA its New Drug Application (NDA) for AFREZZA, citing data from 53 clinical studies. A year later, in March 2010, the agency sent its first Complete Response Letter (CRL) back to the company. A CRL is not good news, since it essentially denies approval of the original application and states what would need to be done to deal with the issues the CRL raises. In addition, the FDA does not guarantee that addressing all of the questions posed in the CRL automatically means a new application will be approved.

Pfeffer and his colleagues may have wished to focus on insulin action, but the FDA chose to focus on the delivery device, as well as on some other issues that were less centered on therapeutic benefits. The primary concern raised in the first CRL was that the inhaler Mannkind used in the trials was not the same as the device they planned to use when the drug was rolled out to patients. Although both inhalers were made by the same company, the models were somewhat different. During the year that passed while waiting for the FDA response, Mannkind had developed a new, smaller, more efficient, more convenient and less costly inhalation device affectionately dubbed “Dreamboat” inside the company. (Somehow, the nickname leaked, and is now routinely used in articles and reports about AFREZZA.)

After Mannkind addressed the questions that were raised in the CRL — by making a resubmission using Dreamboat — it looked likely that the FDA might approve the product by December 2010. But no approval came. Instead, after telling Mannkind that it needed an additional three to four weeks to finish its review, the FDA sent a second CRL on January 18, 2011, stating that the data presented was still not sufficient. The FDA then required two additional clinical trials using the Dreamboat inhaler, in part to compare it to the earlier inhalers and also to assess “performance characteristics, usage, handling, shipment and storage.” The agency also asked for an update of safety information related to AFREZZA, as well as a plan for user training and changes to the proposed labeling of the device, blister pack, foil wrap and cartons.

No one knows why AFREZZA went from an apparent sure thing to a rejection between Christmas 2010 and mid-January 2011. The FDA does not disclose internal discussions leading to either an approval or a CRL. But an FDA employee, who was later convicted of using inside information to profit from buying stock in publicly traded companies whose drugs were about to be approved, purchased a large number of Mannkind shares in early January, a clue that suggests approval was imminent. Instead, it was back to the drawing board for AFREZZA. Had Mann not invested so much of his own money to keep the company afloat, it surely would have died long before even the second FDA “No.”

As one would expect of someone who knows he must be careful not to offend the agency that can make or break his product, Mann is cautious when asked for his reaction to the delays. “All I can say,” he replied, “is that the regulatory process in this country is rather complex and certainly needs streamlining. There’s no reason that it should take 15 years and 1.5 billion to 2 billion dollars to take a drug to market. But we are risk-averse as a society, and that’s the world we live in, so we have to adjust to it.”

The Last Mile?

AFREZZA’s two new studies finished enrollment in the fall of 2012, and the last patients for those trials won’t finish until May and early June 2013. If the complete reports are submitted to the FDA this summer, it is quite likely that, on its third attempt, AFREZZA could gain approval and go to market in 2014. Mannkind won’t have too much trouble meeting early demand: it built a plant to manufacture the product in Danbury, Conn., a couple of years ago and purchased enough leftover insulin from Pfizer to create $10 billion worth of marketable AFREZZA. The leftover Exubera insulin is currently stored in Germany.

Because these two new trials are blind studies, Mannkind won’t know the actual outcome details until after the last patient finishes. Although the company doesn’t know who the test subjects are, those who participate in the tests do not sign secrecy agreements, and some of them get in touch with Mannkind from time to time. In fact, this article was prompted by an e-mail from one of the Type 1 subjects who found AFREZZA to be very effective.

If approved, AFREZZA is obviously an alternative to bolus injections or infusions for Type 1s, but the Type 2 population might be the biggest winners. . . . Offering these patients an alternative to injecting insulin might also significantly increase both acceptance of and adherence to prescribed insulin therapy.

Based on what he has heard from some of the trial subjects who reached out to the company, Mann is confident. “We will have stupendous results in both of them [the trials],” he predicted. “There have been no safety signals of any kind.” He is probably correct about safety and efficacy: after all, neither CRL has raised questions about how well the product works or — most importantly — its claims of rapid onset absorption and equally rapid decline.

Who will benefit most from AFREZZA? If approved, it’s obviously an alternative to bolus injections or infusions for Type 1s, but the Type 2 population might be the biggest winners. More doctors than ever believe that aggressive treatment of high glucose levels in Type 2 patients, using insulin at the beginning of their therapy rather than as a last resort, is the fastest way to get their diabetes under control and allow a healthy diet and regular exercise to work best. Offering these patients an alternative to injecting insulin might also significantly increase both acceptance of and adherence to prescribed insulin therapy.

There is no question that AFREZZA would have to launch a significant awareness and education effort aimed at doctors, particularly primary care physicians who diagnose and continue to treat a majority of the Type 2 patients. It may not be simple or easy to introduce a sea change in insulin therapy, particularly to physicians who are familiar with shots, but convenience and needle aversion among patients would probably win out in the end.

Will Mann finally rest from his labors if AFREZZA is approved? It’s not likely. It doesn’t take much prompting to get him going on the merits of a simple, affordable patch insulin pump, or on the benefits of inhaled drugs in treating various other diseases. To a man blessed with brains, an inexhaustible curiosity, and significant capital resources earned from his many successes, there’s always another rainbow, and another pot of gold, just over the next hill.

Thanks for reading this Insulin Nation article. Want more Type 1 news? Subscribe here.

Have Type 2 diabetes or know someone who does? Try Type 2 Nation, our sister publication.